By Kristine Magnesen, Communications Advisor

“The story behind the Sami flag is actually kind of wild,” Synnøve Persen says. In the summer of 1977 the students at the National Academy of Fine Arts arranged a sales exhibition to earn money for a trip to Jølster, to visit the area where their professor of painting, Ludvig Eikaas, came from. “The exhibition was such a success, and we made so much, that we were able to travel even farther west. We ended up taking a boat from Bergen to Torshavn on the Faroe Islands.”

The idea was born

Since 1948, the Faroe Islands have been a self-governing territory within Denmark, and their autonomy is strengthened by the fact that they have their own flag and official language, Faroese. In this island archipelago west of Norway, Persen met local artists who spoke of their independence and Faroese identity with pride. “That lit a spark in me,” she relates.

Returning to Bergen by boat was not an option. “The trip over was horrible. We threw up and felt very seasick.” On the flight from Torshavn to Copenhagen she looked out at the sea and parts of Norway. The Sami people and the Sami homeland, Sápmi, lacked a way to mark their sense of community and identity. “I thought ‘my country has no colours,’ and that’s how the idea was born.”

A blueprint for a Sami flag

Back in Oslo, Persen began her final year of studies in the graphic art programme. “I wasn’t planning to work with graphic art, but it was important for me as an artist to be familiar with other techniques, including graphic art. I used the colours of the kofta, the traditional Sami jacket we wear in the area I come from, Porsanger. Karasjok uses the same colours, as does Utsjok, over the border in Finland.”

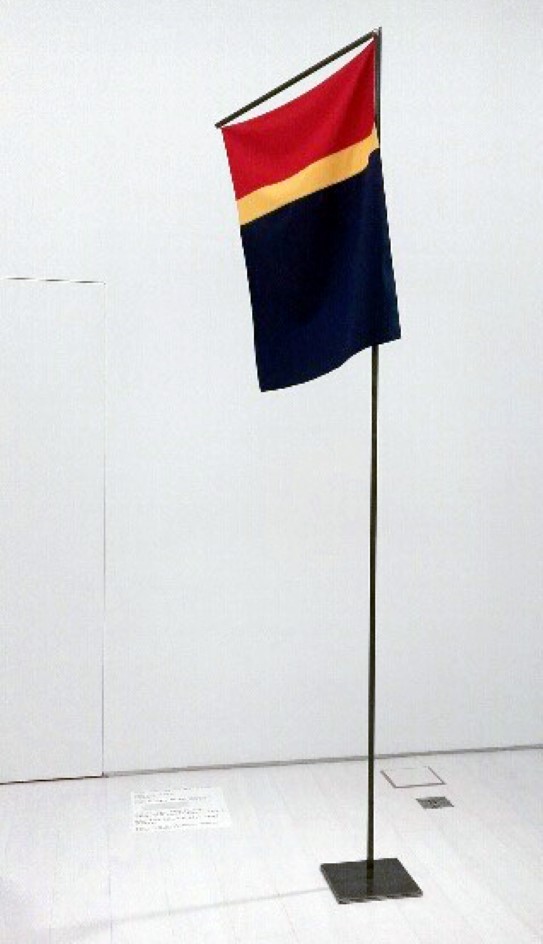

The silk-screened design in red, yellow and blue was given the title Utkast til samisk flagg [Blueprint of a Sami Flag]. Persen also sewed a cloth flag to carry in the May 1 parade in Oslo.

Symbol of protest

In the late 1970s, several other Sami flag designs were proposed. During the demonstrations against dam construction plans in Alta in the late 70s and early 80s, Persen’s version of the flag was raised. “I thought for a long time that the flag I had made was used in Stilla. It wasn’t, but they had used my blueprint as a template.”

Thus Persen’s flag became a symbol, not only of the Sami people, but also of the fierce protests against hydropower development in Finnmark, northern Norway.

The Masi Group

“I have always been something of an activist, I think. I’ve invested a lot of energy in being a pioneer and trying to make things better,” Persen says.

In 1978 she was one of the founders of Mázejoavku (the Masi Group) along with seven other Sami art students. Arts Council Norway had commissioned them to design the decorations for architect Kjell Lund’s Láhpoluoppal Primary School in Kautokeino. “We had no experience with either decoration or major commissions. We were still just students. It took several years and a lot of arguments, but we did produce something in the end. Our group was started as part of the same process.”

“Our goal was ‘art to the people’. We had no ambition of becoming famous ourselves. We wanted to make art accessible to everyone.”

– Synnøve Persen

Art to the people

The Masi Group decided that the struggle to promote Sami art had to be fought from Finnmark, so they all moved there. “That was very much in the spirit of the times. In a way we became foot soldiers for art,” Person continues.

They established workshops in Máze (Masi) and Guovdageaidnu (Kautokeino), and also travelled around in a small bus. “We held exhibitions in villages where they had never had an art exhibition before, and where there probably hasn’t been one since.”

They continued for several years, but trying to earn a living as idealists became too difficult.

Persen was one of the founders of Sámi Dáiddačehpiid Searvi – the Sami Artists’ Union – in 1979. This association of artists from the entire area of Sápmi works to establish support schemes for Sami art, and offers courses and training for artists from all countries with a Sami population.

Opposition to the Sami flag

When Persen wanted to include her flag among the works in the exhibition Sámi Álb’mut (The Sami People) at the Norwegian Museum of Cultural History in 1978, the director unequivocally refused. Photographer Paul Anders Simma, one of the others exhibiting works there, had recently been in Russia and had taken pictures of Sami people there. This was the first time that photographs of Sami people on the Russian side of the border were going to be shown in Norway. Persen and Simma banded together and threatened to withdraw all their works if the flag was not included. “The flag stayed, and I can’t recall any reactions to it.”

Her most vivid memory of the exhibition is a collection of duodji (traditional handicrafts) from Sweden. “I thought it was beautiful and impressive, and it made me very proud to see it.”

Invitation to documenta

After the exhibition at the Norwegian Museum of Cultural History, Persen did not see the flag again for 25 years. “I didn’t bring it with me when the exhibition was packed up.”

Luckily someone had taken good care of it, and gave it back. Because when one of the world’s largest exhibitions of contemporary art, documenta, contacted her in 2016, Persen once again needed to produce her country’s colours.

Prior to receiving the invitation she had been showing an international delegation around the old workshops in Máze. Her head and her heart had been transported to a different time. The encounter with the workshops the Masi Group had left behind over 35 years previously made a deep impression. “Paper and drawing equipment were lying on the tables. It looked as though we had been there yesterday! I showed them around and talked and talked and talked.”

It was not until afterwards that she realised that the delegation consisted of the directors of documenta.

Interpretations of the flag

Along with two other former members of the Masi Group, Britta Marakatt-Labba and Hans Ragnar Mathisen, Person was given the task of interpreting the theme Sápmi – getting there and away for the exhibition, which is arranged every five years. “I just had to throw myself into the work – all I had were the time I’d spent and the path I had followed. Using the flag I had made in 1977 as my starting point – who was I as an artist, a Sami artist and a human being in the autumn of 2016?”

When working on her contribution to documenta 14, Persen drew inspiration from works such as Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III by Barnett Newman. She had seen it at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam a few years earlier. “It’s a large work using exactly the same colours.”

The result was interpretations of the 1977 flag in the form of the paintings En tricolor [A Tricolour], Rød – blå – rød [Red – Blue – Red] and Gul – blå – gul [Yellow – Blue – Yellow].

Mounted beautifully in Athens

documenta 14 opened in Athens, Greece, in April 2017, and exhibitions were also held in Kassel, Germany. Persen’s works were shown on the 5th floor of the National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST) in Athens. “I have never seen my works mounted more beautifully than they were there. You can hardly believe what you’re seeing. They had even painted one of the columns in ‘my’ shade of red.”

Before her works were mounted, Person was asked whether she thought that the Sami art should be shown together. “I absolutely did not want that. Then you’re just part of the ‘Sami artist’ group.”

Works that tell a powerful story

The National Museum purchased both the silk-screen print and the hand-sewn flag after visiting Persen’s workshop in 2017. The museum’s curator, Randi Godø, describes the workshop as having tall, white walls with windows allowing close contact with the natural surroundings – a classic setting for a painter. Representatives of the museum know it creates expectations of a purchase when they visit a workshop, but it is primarily the conversation with the artist about art that is important. “We rarely ask about purchasing something there and then; that is something we discuss among ourselves in the museum afterwards,” she explains.

All purchases must go through a process detailing the reasons to buy, followed by a discussion and approval. It was easy to present the arguments in favour of including Blueprint for a Sami Flag in the museum’s collection. “Persen is an artist who was not yet represented in the National Museum’s collection. That was rather strange, actually, as she has been a very visible figure both with her art and as a champion for Sami life and culture. And this flag is a symbol of the Alta demonstrations, so we felt that we were also getting a work that was meaningful with regard to important events in Norwegian history,” Godø says.

Will be exhibited in the new National Museum

Blueprint for a Sami Flag will be exhibited in the new National Museum when it opens in 2022. “I hope that neither my art nor that of other Sami artists will be shown together in a room dedicated to Sami works. In my view it is more interesting to see Sami art in relation to other art and other artistic styles,” Synnøve Persen concludes.

Synnøve Persen

- Artist, poet and organisation builder

- Born 22 February 1950 in Bevkop, Porsángu (Porsanger)

- Studied at Einar Granum School of Fine Art (1971), Trondheim Academy of Fine Art (1971–72) and the Norwegian National Academy of Fine Arts (1972–78)

- Participated in demonstrations against the hydropower development in Alta, 1970s and 80s

- Head of Sámi Dáiddačehpiid Searvi (the Sami Artists’ Union), 1980–83 and 1989–93

- A key figure in organising the Sami Centre for Contemporary Art and the Karasjok Art School

- Has held exhibitions, carried out decorating commissions and received distinctions including the Arts Council Norway Honorary Award and the Royal Norwegian Order of St Olav (2018)

- Represented at documenta 14 in 2017

- Blueprint for a Sami Flag will be exhibited at the new National Museum when it opens in 2022

References:

Documenta 14.de: Sámi Artist Group (Keviselie/Hans Ragnar Mathisen, Britta Marakatt-Labba, Synnøve Persen)

NRK.no: Sameflaggets opphav diskuteres [The origins of the Sami flag are discussed], Kunstskole til Karasjok godkjent [The Karasjok Art School is approved]

Who's Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Sámi Dáiddafestivála [Sami Art Festival]: Samisk Kunstnerforbund [the Sami Artists’ Union]

Store norske leksikon [The Great Norwegian Encyclopedia], snl.no: Synnøve Persen, Ludvig Eikaas, Færøyene [the Faroe Islands], Alta-saken [the Alta movement], duodji [Sami handicraft], Sameflagget [the Sami flag]

Wikipedia.com: Synnøve Persen, documenta, Lahpoluoppal skole [Láhpoluoppal Primary School]

Wikiwand.com: Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue