Many people probably associate Queen Maud with elegant evening gowns, made by the most extravagant materials. But the iconic queen also had a sporty side and, not least, stylish clothes for every sport occasion.

Text by Collections Registrar Janne H. Arnesen

On 28 October 1895, a royal engagement was announced in London: that of Princess Maud of Wales and Prince Carl of Denmark (later King Haakon VII of Norway). The bride's new wardrobe was finished during the spring and summer of 1896, and was extensively discussed in the British press. The Queen magazine commented that it was a stylish wardrobe that included more casual wear than party dresses, which perhaps was unexpected for a British princess. The wardrobe included several walking suits for daily use, travels and sports.

Public and private queen

Maybe you still associate Queen Maud with glamourous evening gowns with beading and lace, complemented by glittering tiaras, jewellery and court trains? This is how she often appears in official photographs and paintings, and it is this part of the Queen's wardrobe that will greet the audience in the new National Museum in 2022: The Queen's official role, when representing Norway. Her more athletic side, with a love for cycling, skiing, skating and horseback riding, is thus an interesting contrast. When you look at the Queen's preserved wardrobe as a whole, it reflects what The Queen magazine reported in 1896: casual wear is well represented.

Queen Maud's wardrobe as we know it today was donated to the Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in two parts. The first donation was made by her son, H.M. King Olav, in 1961. It included attires considered to be of national importance: her coronation dress, court trains, Norwegian folk costumes, evening gowns, and selected sportswear.

The second donation was made in 1991, after King Olav's death, by his three children and with a selection done by H.M. Queen Sonja. This donation included beaded 1920s dresses, smart dress suits, shoes and bags, and even more sportswear. Some additional garments have been received from other sources. Together, the wardrobe provides a unique insight into Western fashion as it developed from 1896 to 1938. Anne Kjellberg was the responsible curator at the time of the 1991 donation, and it is largely due to her thorough work on the wardrobe we today have a good overview of the garments: who made them, when they were used, and on what occasions. Queen Maud's sports wardrobe is therefore also well documented.

Rural life gives way to city life

"Every day we cycle a lot before dinner & come back quite late, we live a wonderful life & do exactly what we want", wrote the newly wed Princess Maud in a letter on 20 August 1896. She and her husband had received the country estate Appleton as a wedding gift, and spent much time there after the wedding. The press commented that the princess had not followed the risqué trend of wearing trousers when cycling, and opted instead for long skirts and tailored jackets. She also got praise for her practical cycling hats.

At Appleton and the neighbouring estate Sandringham, which belonged to Queen Maud's parents, it was possible to skate on the local pond when weather allowed it. In the 1890s, a series of skating photos were shot, photos that today are a part of Queen Maud's private albums in the Royal Collections:

It is hard to tell which of the three princess sisters is pictured here, but both ice skates and roller skates are preserved in Queen Maud's wardrobe. Two pairs of ice skates are dated to sometime between 1900 and 1920, while the roller skates are from sometime between 1896 and 1913. All three pairs consist of a metal base screwed onto a high-heeled leather boot. A balancing act in more ways than one!

On horseback

Queen Maud was also a well versed equestrian from early youth. Like the other women of the family, she rode a side saddle. This meant that both knees were on one side of the saddle, placed around two pommels. The skirt was usually constructed accordingly, tailored around the knees, longer in the front than the back, and draped into place. Especially designed trousers was sometimes worn underneath in case the skirt shifted. Several of Queen Maud's riding outfits have been preserved. A brown suit made by John Busvine & Co around 1920 shows signs of wear and tear, as well as alternations.

After some time in England, the newlyweds moved to Denmark. They were installed in an apartment in Bredgade, in the city centre of Copenhagen. Her husband spent a lot of time in the Navy, and Princess Maud expressed a sense of unhappiness. She felt lonely, and the city’s narrow cobblestones streets didn’t quite allow the cycling, horseback riding, skating and general active life she was used to. "She didn’t enjoy the winters in Denmark, and she regularly complained about the weather in letters she sent to the family back in England", Kjellberg writes about Queen Maud.

Winter joy in norway

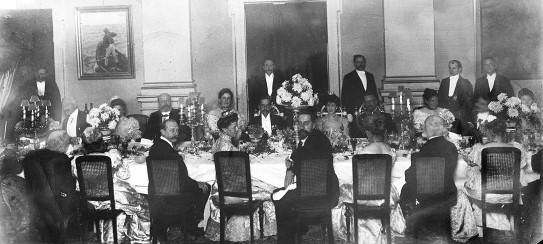

With this in mind, it is easier to understand why Queen Maud seemed ready to embrace Norway, as the couple accepted Norway's throne in 1905. The new royal couple arrived in Oslo on 25 November 1905. The very next day, 26 November, the Queen celebrated her 36th birthday in a dinner hosted by prime minister Christian Michelsen, in his home:

Shortly after it was time to start exploring everything Norwegian. The royal family was introduced to skiing by polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen and his wife Eva. Eva Nansen was herself a pioneer of women’s skiing, and in 1890 she had accompanied her husband across Norefjell, which was far from commonplace for any urban woman at that time. In 1905 and 1906, the royal couple and Nansen did several ski trips in Oslo and surrounding areas. Some of the trips were documented by photographer Anders Beer Wilse. They also tobogganed at the hills of Holmenkollen. On 22 March 1906, Queen Maud wrote enthusiastically to the family in England: "We lived out of doors & we went on skis & tobogganed & sleighed. It was wonderful in the deep snow & glorious sun".

In 1910, the royal couple was gifted Kongsseteren, the Royal Lodge, from the Norwegian people, and from would spent much of the winters there in the years to come. According to Kjellberg, the queen skied once or even twice a day whenever the weather and schedule permitted. Queen Maud continued to write enthusiastic letters to her family, including one dated 22 January 1914: "Here it is lovely & clear & sunny every single day, so we ski as much as possible."

The main look of Queen Maud's ski outfit from this time followed the same tendencies as her general wardrobe. Between 1905 and 1915, she is photographed in long skirts and tight-fitting jackets or knitted sweaters. But these were often made of thicker, warmer materials than the general wardrobe, and she topped it all off with a sports cap, knitted gloves or mittens, and gaiters.

Glimpse of a sports wardrobe

Large parts of what we today refer to as Queen Maud's wardrobe were made in Great Britain and France. Norwegian producers are in large absent, though with some notable exceptions. Her coronation dress from 1906 was a collaboration between the couture houses Silkehuset Norway and Vernon in Britain. The fashion house Sylvian, which was run by a close friend of the queen, also provided her with a selection of fashion garments in the 1920s. Her two folk costumes from Hardanger and Hallingdal were of course Norwegian. In addition, there is some Norwegian-produced sportswear , although Norwegian producers were not the sole suppliers of these items.

One of the earliest Norwegian garments identified in the wardrobe is a brown fur jacket with gold details. It is dated 1905 and was made by Pels-Backer, which was located on the same street as the couture houses Molstad and Steen & Strøm in Oslo. In a letter dated 17 December 1905, Queen Maud wrote that she wanted to support Norwegian companies by doing her Christmas shopping with them. She also expressed joy at the quality of Norwegian fur, which was superior and less expensive than what she was used to in London. She may have bought the brown fur jacket on one of these shopping trips. In any case, it can be seen in photographs Wilse took of the royal couple in a snow-filled landscape on 14 January 1906:

Queen Maud’s wardrobe contains many British-made wintersport coats dated 1915 to 1935. Two of them were produced by British Vernon, the same company working on her coronation dress. Some sportswear was also made by British Blancquaert, while the makers of several other garments have not yet been identified. The wintersport coats can be seen in several photographs from the 1920s, including the brown ski coat from Blancquaert. It appears in photographs from the Holmenkollen ski jump in the winter of 1923. Here it is combined with knitted mittens with motif of the “Norwegian Star”.

Radical skiing trousers

After cycling, riding, skating and skiing in skirts since the 1870s, the queen ordered a ski suit with trousers in the 1930s. This was a big leap and a brave choice for a woman in her mid-sixties, a woman who had been raised in a Victorian era where trousers had never been an option. At the same time, it must be mentioned that ski trousers were more the norm than the exception amongst Norwegian skiers by the 1930s, and the queen was probably one of the last to adopt this fashion. Sports suits had also long offered alternative models with trousers under the skirts for the sake of warmth and decency. Nevertheless, this is one of the very few documented cases of trousers in Queen Maud's wardrobe. The ski suit was made by the Norwegian company Frode Braathen, who also sold his creations through Patou in Paris. The ski suit is dated to around 1935, and made of sturdy brown wool gabardine. The museum's inventory card from 1962 reveals two additional handwritten notes, saying it was: "HM Queen Maud's last and best", and further that she is photographed in the ski suit in a private photo from 1935.

Carving the first track?

Many of the preserved garments and attires from Queen Maud's wardrobe has been identified through photographs and written sources. They tell of a sports-loving woman who was physically active for most of her life, and who became especially fond of winter sports in Norway.

Anne Kjellberg writes that Queen Maud probably should not be considered a pioneer within neither sportswear nor the sports movement overall, but, she adds: "She was one of the enthusiasts in the first big wave of female cyclists, and thus served as an example for others. Her skiing may also have been influential in Norway. For women who were still reluctant to go skiing in 1905, Queen Maud set an example they could follow."

Sources

- Anne Kjellberg: Dronning Maud. Et liv – en motehistorie, Grøndahl Dreyer (1995)

- Anne Kjellberg and Susan North: «Style & Splendour. The Wardrobe of Queen Maud of Norway", Victoria & Albert Museum (2005)

- Astrid Bugge: Bydamer i «touristinde-dragt, i By og Bygd (1958)

- The Royal Collections: Queen Maud's private photo album

- Royal Collection Trust: Princess Victoria's private photo album

- Further photos from Digitalt museum, Nasjonalbiblioteket and Scanpix

- Annemor Sundbø: «Koftearven. Historiske tråder og magiske mønstre». Gyldendal (2019)