Text by Senior Curator Exhibitions and Collections Andrea Kroksnes

Louise Bourgeois and Alina Szapocznikow met in 1969 in Carrara, Italy, where they were both working at the marble quarries. The small Tuscan town settled between the impressive mountains of white marble and the summer-crowded beach resorts of the Ligurian Sea, like renowned Viareggio, was a fashionable meeting place for contemporary artists from around the world. Bourgeois had come on the advice of her friend, the American sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, and worked at various quarries and foundries in Carrara and nearby Pietrasanta for several weeks at a time from 1967 until 1971. In this intimate and nourishing setting far away from home, it was easy to make acquaintances and exchange ideas and information. The list of artists she met ranges from the younger Polish artist Szapocznikow, the Japanese sculptor Isamu Noguchi, and the well-established English sculptor Henry Moore, whose studio she rented after he left. In letters to her husband Robert Goldwater, she described these inspirational interactions. At the same time, she was also aware that her colleagues might get inspired by her work, and she expressed an almost neurotic fear of being copied.

A new friendship

When she met Alina Szapocznikow, the two artists immediately became close. Both were still little-known figures in the international art world and probably shared the experience of struggling as female artists in a male-dominated art world. Szapocznikow had gained some attention when she impressed the jury of the Copley Foundation, consisting of Jean Arp, Marcel Duchamp, and Max Ernst, among others, and won their prize in 1966. Bourgeois was not recognized internationally at the time, despite several solo exhibitions in New York and her participation in the now famous exhibition Eccentric Abstraction curated by American art historian Lucy Lippard in 1966 at New York’s Fischbach Gallery.

A possible rivalry

Bourgeois wrote home about one of their visits together: “This afternoon… Alina has invited me... to show me her catalogues and pictures. It is body parts immersed in moss like Gallo style + Marisol but better... talking freely she told me […] that she had spent 5 years between 13 and 18 at the Auschwitz camp.”

Only a few days later, the intimate connection turned into rivalry and suspicious manoeuvring on Bourgeois’s part.

"I believe that [Alina’s] energy and ambition are unsurpassed to the point of being obsessive – Well I didn’t show my roll construction to [her] because she could make a more interesting use of it!?!?"

Married to one of the foremost scholars of modern art, and having studied art history extensively herself, Bourgeois was well-aware of theories of modern and avantgarde art and its absolute mandate for newness and originality. “What modern art means is that you have to keep finding new ways to express yourself, to express the problems, that there are no settled ways, no fixed approach.”

Art reunites

In spite of Bourgeois’s caution, the fact that Szapocznikow and Bourgeois shared such intimate conversations early on in their friendship could indicate that the two women were close and trusted each other. It is also a fact that Bourgeois was too interested in Szapocznikow and their inspiring artistic exchange to end their friendship. Their connection was mutually felt, and they were in touch again after their encounter in Carrara when both were in Paris

Following an evening with Szapocznikow and her friends, Bourgeois wrote home, invigorated: "Nobody sells; each artist shows to the others. There are very beautiful exhibitions and I am happy to have made the trip".

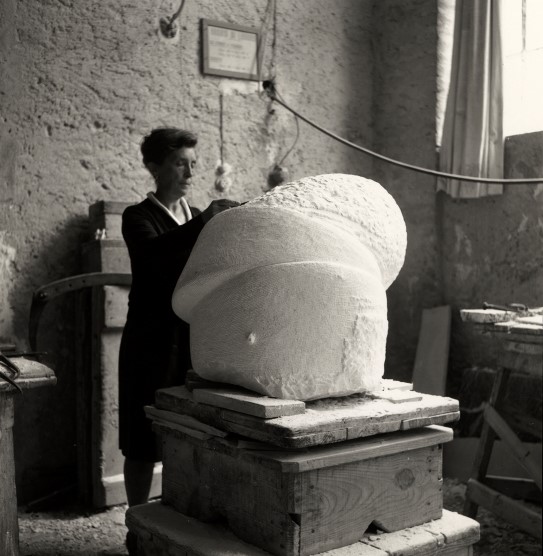

Szapocznikow introduced Bourgeois to friends, such as Roman Polanski and the polish artists Magdalena Abakanowicz and Zofia Butrymowicz. She also gave Bourgeois two of her colored polyester resin lamps as a present, and Bourgeois returned the gesture of friendship by sending Szapocznikow a gold patina version of her sculpture Sleep (1967–68). The photo of her and her enlarged “sleeping” phallus in Carrara in 1967 might have inspired Szapocznikow to have a photo taken of her working on Big Bellies in 1968.

Latex, clay and passion

It was not only the shared situation of being women sculptors in an almost completely male dominated scene that brought them together, but moreover their interest in similar artistic questions, concretely when it came to materials and techniques as well as content. Bourgeois had experimented with latex and clay in works that were included in Eccentric Abstraction.

She had always been very passionate and studious about learning new materials and techniques. One of her earliest works in latex is Soft Landscape (1963), and in 1965 she made a work in resin titled Resin Eight. From 1965–67, she taught sculpture at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where she may have continued testing new materials. It seems like a lucky coincidence that Szapocznikow also experimented with casting and coloring different polymers and polyurethanes. By the time she arrived at her Lampes-bouches in colored polyester resin in 1967, she had become an expert in resin casting. The body in its most erotic as well as abject forms was central to both artists at the time. They shared not only new materials but also subject matter before they even met. Their meeting must have contributed to reassure their paths and help mature their individual practices.

The works from a lifelong collaboration

And from then on, the two artists mutually inspired each other. Szapocznikow’s sculpture Under the Cupola (the Metamorphosis) (1970; ill. 123) in polyurethane foam and nylon stockings suggests that she was familiar with Bourgeois’s Avenza (1968–69; ill. 01) and Cumul (1969) works. The title Avenza is taken from the Avenza neighbourhood in the city of Carrara, where they met. Bourgeois began experimenting with what she called Soft landscapes in latex some years earlier and now translated them into marble and bronze. She had also translated her sculptures Sleep II (ill. 66), Germinal, and Tits (ill. 73) into marble during her first trip to Pietrasanta in 1967. We do not know if Szapocznikow knew these works by Bourgeois, but she started with her belly sculptures that resemble Sleep a year later, using the new technique of colored Polyurethane foam.

Bourgeois’s work Arch of Hysteria (1993)—a full body cast of her assistant and confidant Jerry Gorovoy in an extreme backbend—could be a reference to Szapocznikow’s Piotr (1972), made just one year before she died at age 46. It is a life size cast of her adopted son, bending his head and chest backwards, eyes closed as if in ecstasy. Bourgeois received her last exhibition catalogue, sent by Szapocznikow’s husband, shortly after her death in 1973.

This is a text from the exhibition catalogue Louise Bourgeois. Imaginary Conversations (2023) which is available in the museum shop or in the online shop.

Copyrights:

* Alina Szapocznikow, Sous la coupole (La métamorphose) (Under the Cupola [The Metamorphosis]), 1970. © Alina Szapocznikow / ADAGP, Paris / Courtesy the Estate of Alina Szapocznikow / Piotr Stanislawski