Text by Communications Advisor Ellisiv Brattfjord.

Hertervig did not render the landscape as realistically as possible. He filtered what he saw and therefore presents you with a more personal interpretation of his experience of the landscape. Hertervig's paintings express the artist's inner and emotional landscape rather than the external and realistic.

Ellen Lerberg, Senior Curator Learning at the National Museum.

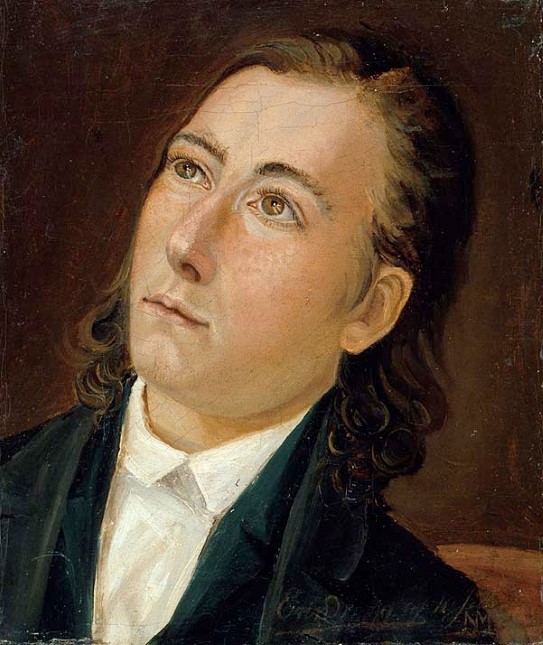

Lars Hertervig was born in 1830 in Tysvær in Rogaland County of humble origins. His family were Quakers, which according to Lerberg may have influenced his art:

Quakers cultivate the divine light, just as Hertervig did. The compositions are often calm and invite reflection.

Unreal landscapes

Like most national romantics, Hertervig was passionate about the magnificent and the sublime in nature. But he stands out. There is a hazy, luminous and dreamlike quality in many of Hertervig's paintings. According to Lerberg, it is almost as if he were a neo-romantic before neo-romanticism emerged and which later focused on subjective artistic expressions, emotions and imagination.

The paintings have a mystic atmosphere. They can be luminous with sparkling sea and sun, or dark and shadowy. His style was more melancholy than that of Gude, who was more clear-cut and unequivocal.

Ellen Lerberg

The new generation

The young Hertervig's talent was discovered early. As a 16-year-old in Stavanger, he took lessons from a master painter and received drawing instruction. He then attended the Drawing School in Kristiania, where he was taught by Johannes Flintoe and Joachim Frich, among others. He was determined to become either a famous painter or nothing.

Hertervig seemed to be destined for a brilliant career and was taught by Hans Gude in Düsseldorf. Kitty and Alexander Kielland were among his benefactors.

"'Here comes the new generation – the new hope!' was how the talent of the then 22-year-old Hertervig was described at the Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts", Lerberg says.

Hertervig painted at the same time as August Cappelen and Johan Fredrik Eckersberg. He painted in a time when the human race was regarded as the custodian of nature but also in a time when nature began to be explored scientifically.

"The trolls of superstition gradually disappeared, and it was understood that the mountains were actually made of stone. But there was still some mysticism in the artistic view of nature," says Lerberg.

Rogaland's mighty landscapes

Unlike many other national romantic painters, Hertervig did not turn to Hardanger and Sogn to find his subjects. It was his home districts in northern Rogaland and Sunnhordaland that appealed to him the most, preferably landscapes just before the storm breaks.

Rogaland and the region's varied coastal landscape remained cherished subjects for Hertervig throughout life.

The rendering of the light, the contrasts between light and dark, combined with a characteristic smoothness and lightness and a dominant blue colour, soon earned the paintings the label "the blonde fjord paintings".

In the summer I often see typical sheer 'Hertervig clouds'

Ellen Lerberg

"The sky, the clouds and the light testify to the eternal powers of nature, that is, those not bound by the earthly and the transitory", writes art historian Holger Koefoed. This romantic longing for light is evident in Borgøy (1867), where Hertervig painted his birthplace the way he imagined it, not the way it actually appears. Here, mountains, fjords, clouds and sky unite in harmony.

Melancholia

The artist was marked by more than just a talent for magnificent and contrasting compositions of nature. He struggled with hallucinations and also became ill from not always being able to complete the paintings he began. He was diagnosed with "melancholia" and "dementia". Today these can be translated to depression and a form of schizophrenia, although some also believe that Hertervig was a victim of the ignorance of mental health of the day. For some time several art historians have believed that Hertervig's illnesses can be seen in his paintings. According to Holger Koefoed, in Lars Hertervig. Painter of Light (1984), the art of Hertervig became "a much needed escape, a place where he could be entirely himself".

Koefoed continues: "Hertervig became the Norwegian van Gogh. His life was a typical example of a modern artist's fate; poor and misunderstood by his contemporaries, but achieving fame after death – and then with mental illness as an interesting extra ingredient". Koefoed believed that this myth was created to conceal the harassment Hertervig suffered during his life.

In more recent times, many believe that Hertervig's more unconventional renderings of nature were actually a renewal of romantic art and a foreshadowing of modernism and artists such as Paul Gauguin.

Hertervig was admitted early on to Gaustad Psychiatric Hospital in Oslo. He was eventually discharged as "incurably ill" and moved home to Stavanger and then to Tysvær, dependent on charity due to his hopeless and stigmatising diagnosis. Many wanted to help the artist financially, but he refused to accept gifts.

"... the disease caused Hertervig to be excluded from contemporary art and art development in Norway as well as abroad", writes Magne Malmanger in Lars Hertervig. The Outer and the Inner Landscape (1992).

It may have been this isolation from the rest of the art world, and from the world at large, that played a part in making Hertervig's images special. He focused on cultivating his own natural experiences in the paintings from his local area and received little input from others.

Home-made paper

For the last 30 years of his life, he could no longer afford to paint with oil on canvas. The works from this period were painted with watercolour and gouache on paper that was actually intended for other purposes, such as wrapping paper, tobacco paper, wallpaper fragments or newsprint. For some of the paintings, he built up thick layers of different papers which he then glued together using rye flour paste he cooked himself.

Towards the end of his life, Hertervig made a living by chopping wood and doing various practical jobs for others in Tysvær. He also decorated furniture. Hertervig lived alone all his life and died in Stavanger in 1902.

Hertervig inspired several artists, including Rolf Nesch, Frans Widerberg and the Danish painter Per Kirkeby. Jon Fosse wrote a novel about the artist, which also became an opera. Theatre, poetry and several songs have been written about the artist's life and art. Despite inspiring many after his death, Hertervig unfortunately never gained true recognition as an artist in his own lifetime.

In the new National Museum Lars Hertervig will have a central place in the collection exhibition, sharing a room with, among others, J.C. Dahl, Knud Baade and August Cappelen. Here you can sit down in peace and quiet and enjoy nature.

See all the digitalised works by Lars Hertervig in the National Museum's collection.

Sources

- Ellen Lerberg, senior kurator formidling i Nasjonalmuseet

- Holger Koefoed, 1984, Lars Hertervig. Lysets maler.

- Reidar Nedrebø & Anne Grete Honerød (red), 1992, Det ytre og det indre landskap.

- Peter Nørgaard Larsen & Sven Bjerkhof (red.), 2007, Naturens speil. Nordiske landskap 1840–1910. [Utstillingskatalog]

- snl.no/nyromantikken

- nbl.snl.no/Lars_Hertervig

- no.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lars_Hertervig

- nkl.snl.no/Lars_Hertervig