A kitchen for the modern woman

Sometimes described as a “laboratory of housework”, the Frankfurt kitchen was designed as a replacement for the traditional kitchen that would rationalise the everyday life of the modern woman.

Text by the Editorial Staff

The National Museum’s Frankfurt kitchen is one of the most complex works in the collection. Before the opening of the new museum in 2022, an endless nubmer of components was restored and the kitchen was reconstructed to be displayed in its original form. Explore a fascinating piece of design and kitchen history!

The first Frankfurt kitchen was designed in 1926. The aim was to rationalise daily life – making it more efficient, more hygienic and less time consuming. Our own kitchen was produced in 1960.

Eliminate unnecessary movement

The first Frankfurt kitchen was designed in 1926 by Austrian architect Margarete (Grete) Schütte-Lihotzky. The goal was to rationalise daily life – making it more efficient, more hygienic and less time consuming. The ideas behind the kitchen were implemented by the engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor.

These were based on principles concerning the efficient performance of tasks, both in the home and the workplace, so as to eliminate unnecessary movement. The layout also reflects the rationalistic ideas of the domestic scientist Christine Frederick.

In designing the kitchen, the architect Schütte-Lihotzky drew inspiration from the kitchens of restaurant cars in long-distance trains. Her research also included interviews with housewives and women’s organisations.

About the Frankfurt Kitchen

- The kitchen purchased by the National Museum is one of a series of 10,000 installed in the Frankfurt area in the 1920s. It was designed in 1927–28 by the Austrian architect Margarete (Grete) Schütte-Lihotzky for the architect Ernst May’s residential project “Das Neue Frankfurt”.

- The prefabricated, mass-produced kitchens were installed in the Frankfurt area. The National Museum’s specimen is from the Römerstadt district.

- It was intended as a “compact domestic laboratory” that would rationalise daily life, improving efficiency and hygiene, and making kitchen work less time consuming.

- The Frankfurt kitchen replaced the traditional kitchen, which was a place for preparing food, eating, socialising, doing laundry, bathing and even sleeping.

- The design is inspired by the kitchens of restaurant cars on long-distance trains.

- The kitchen provided a model and a standard for working kitchens throughout the 20th century and right across Europe.

- Several major museums have acquired Frankfurt kitchens, including MOMA and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

All the drawers and cupboards reachable from a swivel chair

The first Norwegian example of a compact “laboratory kitchen” dates from three years after the one created by Schütte-Lihotzky. It was designed in 1929 by Edvard Heiberg for the house of his father, city councillor Heiberg, at Blindern, Oslo. “The kitchen has a fairly small floor area and is therefore efficient. From a swivel office chair in front of the electric stove, the housewife can reach almost all the drawers and cupboards in the kitchen,” writes the architect (Ulf Grønvold, Arkitekt Lars Backer og hans tid. Oslo: Pax forlag, 2016, 163).

Revealing a female architect’s thoughts on domestic life in the 1920s

As a concept, the Frankfurt kitchen provided a model and a standard for working kitchens throughout the 20th century and right across Europe. In terms of design, it had much in common with the kitchens of Nordic functionalism. Even today, designers and manufacturers still find inspiration in this design icon, which has become a popular subject in life-style research.

“The kitchen is a remarkable piece of design and interior architecture – a fascinating, forward-looking object. It is the modernists’ attempt to rationalise every aspect of daily life. The kitchen reveals the thoughts of a female architect in the 1920s about how life in the home ought to be structured. The woman in the home should have more time, so that she herself can go out to work,” says senior curator at the National Museum, Dr Denise Hagströmer.

In the 1970s and 80s, feminist sociologists argued that although one of the aims behind this compact working kitchen was to liberate women, it proved counterproductive in that it tended to isolate housewives from the rest of the home.

An endless number of components to be restored

Furniture conservator Merle Strätling and object conservator Hanne Skagmo have spent many hours restoring this small, compact household laboratory. The aim of the conservation work has been to reconstruct the kitchen in its authentic condition and with its original floor plan.

The kitchen is a large and complex object consisting of many parts made from many materials with differently treated surfaces. There are work surfaces of beech wood and linoleum, cupboards and drawers of pine and plywood, a metal sink, ceramic tiles on the floor and walls, glass, a radiator, a stove, trimmings, a window, cups, containers, and much more. A Frankfurt stool designed by Schütte-Lihotzky is also part of the interior.

“One of the main tasks in working on this kitchen has been to build up a full picture of the many component parts, what it is we actually have here and what we need to procure. An inventory of this kind helps you to understand the thing as a whole; it lets you see how things are connected and what’s missing,” says conservator Hanne Skagmo.

Should the mark left by the grinder be repaired?

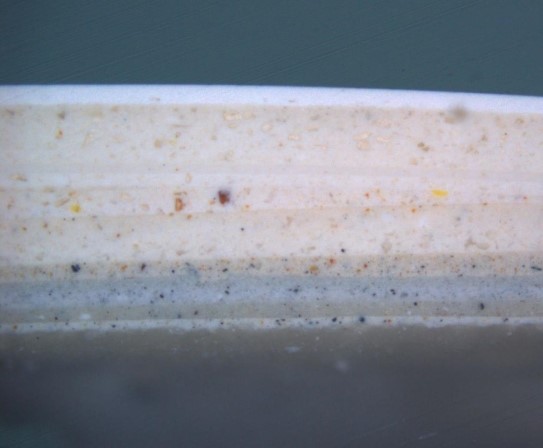

The kitchen has been refurbished several times. Surveys show that in some places there are three layers of paint, in others as many as twelve. Which changes should be retained and which should be reversed? As far as possible, the kitchen should be returned to its original condition, but what was the original condition? What period should we choose to go back to? Which colour palette and array of materials should the various components reflect? What should be repaired and what should be left as it is? How should we distinguish traces of use from traces of damage?

“Traces of use have a story to tell and are very different from damage. For example, in this kitchen there is a hole under the work surface where the clamp of a grinder was attached to the top. Traces of use of this kind will be preserved,” says Skagmo.

Open to changes

Given the many choices that have to be made during preservation work, some of the options have to be rejected. Perhaps we will decide at a later stage that we should have chosen a different worktop. Here we need to take a long-term perspective and to leave scope for new insights that might persuade us to alter the presentation. It is therefore important to retain the possibility to return later on to the options that we reject now.

“There has to be the opportunity to reassess the object at a later date. As far as possible, the preservation methods that we apply should be reversible, leaving the object open to different treatments in the future. This isn’t always possible. Once something has been cleaned, you have to accept the result. But when it comes to which glue you use, you can choose one that can be dissolved again, and you can choose stable materials that retain their properties over time and that tolerate different treatments or can be removed,” says Skagmo.

Up close in the new National Museum

Once installed in the new National Museum in 2022, this compact laboratory kitchen will be available for inspection at close quarters. The installation will also include many of the utensils used in the kitchen.

“Visitors will see a kitchen with many surprising and intriguing features. A kitchen of eight square-metres that remained in use for several generations before being replaced. In fact, for no less than seventy years! How many modern kitchens will survive that long?” asks Denise Hagströmer.

About the conservation of the Frankfurt kitchen

- Object conservator Hanne Skagmo and furniture conservator Merle Strätling have been working together to prepare the Frankfurt kitchen for display in the new National Museum.

- Karen Melching of the restoration firm Kossann & Melching in Bremen, an expert on the Frankfurt kitchen, has been a consultant to the project. She has helped find solutions and shared her experience of working on a similar project at the V&A in London.

- With the help of exhibition technician Christopher Gjerde, the kitchen has been reassembled in modules that make it easier to move and install in the new National Museum.

- For further reading, see Inger Johanne Lyngø: “Husmorens laboratorium – det funksjonalistiske kjøkkenet med eksempler fra Tyskland, Amerika, Norge og Oslo”, Byminner no. 1, 2015, 28-43 (in Norwegian only).