Community architecture

Text by senior curator Martin Braathen

In the exhibition What We Share. A Model for Cohousing the Norwegian architectural firm Helen & Hard has built a new cohousing community. But what exactly is cohousing, and how did this form of housing originate?

In everyday speech the term is used broadly to describe different types of care homes and special needs housing, and housing for certain age groups, and is often used synonymously with ‘communal’. In urban planning, on the other hand, the term cohousing has a clear definition.

What is referred to as the Nordic cohousing community can be dated to around 1970. In 1968, the Danish architect Jan Gudmand-Høyer published the article The missing link between utopia and the outdated single-family house. He wrote about a new form of housing placed between the conventional detached house, which today is still the most common form of housing in the Nordic countries, and the utopian communal societies, where people gathered around a political or religious ideal. Gudmand-Høyer described a form of housing with relatively small private housing units that share large, social communal areas. For Gudmand-Høyer, the social community itself was a necessity in the future he envisioned, where new communication technology would make people want to travel less and become more locally oriented.

The term cohousing community became established throughout the 1970s to define a voluntary association of fully equipped housing units that share common areas and common functions such as workshops, guest rooms and communal kitchens. The cohousing model is built around a volunteer-based social community, often linked to shared meals and hobby activities.

A volunteer-based form of housing

Cohousing communities were of course not the first collective form of housing in the Nordic countries. From the 19th century, for example, a phenomena known as communal kitchens or communal houses arose, where the residents paid for canteen dinners and sometimes childcare. In Norway, we had, among other things, communal kitchens in Oslo, in Balders gate, designed by the architect and city planner Harald Hals, and in Gabels gate. Both were completed in the 1920s.

In Denmark, Centralhuset in Copenhagen was completed in 1907, and in Sweden the best known example is Sven Markelius and Alva Myrdal's functionalist Kollektivhus from 1935 in Stockholm. Many of the communal projects were driven by ideals of liberation of workers and women.

An important difference in the development of the Nordic cohousing model was that the new housing communities which emerged around 1970 differed from the service-based cohousing models, where one paid for communal services. The new cohousing communities also differed from the many experimental, political collectives from the 1960s, where the goal was to challenge the nuclear family and sexual morality. The first two cohousing communities to follow the Nordic model were the Danish Sættedammen (1969-1972) and Skråplanet (1965-1974), both of which grew out of projects involving Gudmand-Høyer.

The first Norwegian example was Borettslaget Bergsligata 13 in Trondheim, established as a political collective in 1972 at a temporary address and which during the 1970s developed in line with the Nordic cohousing model. The cohousing community Kollektivet in Hovseter (1976), was the result of many years of struggle for three women's organisations that wanted to help more women obtain employment. This community was also initially intended as a service-based communal project, but developed into a volunteer-based housing community.

Growth, ownership form and criticism

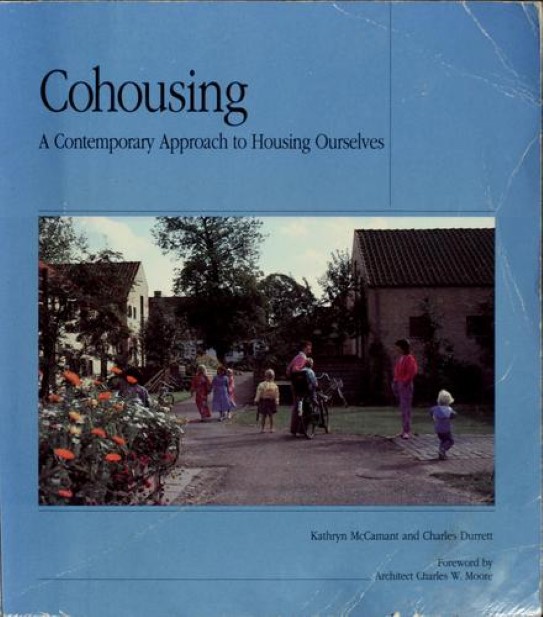

It may be a coincidence that the term cohousing became used internationally to refer to the Nordic region, because the Nordic countries were not alone in developing communal housing models during this period. But the English word cohousing was developed and disseminated by the American architects Kathryn McCamant and Charles Durrett, who studied communal housing in Denmark in the 1980s. They took the concept back to the United States and became influential advocates of cohousing communities outside the Nordic region. Today, there are cohousing communities all over the world – including in the USA, Canada, England and Australia – all of which recognise their origins in the Nordic countries.

A special feature of Nordic cohousing communities, which is not as common outside the Nordic region, is the extensive use of the owner-occupancy model. In the Nordic countries, the ideal of self-ownership was a key element of social democratic housing policy starting in the period after the First World War. This element was based on the principle that no one should be dependent on a landlord. This also became the dominant trend in the cohousing communities that emerged from around 1970 in the Nordic countries. There were several reasons for this: it was difficult to obtain government funding for experimental housing projects, and financing for rental housing was difficult to combine with development processes in which the residents themselves participated in the design of their homes. But the self-ownership model also gave increased ownership of and responsibility for the communal spaces – everyone was obligated to buy and finance a certain number of square metres of the common areas. In this way, self-ownership communities also experimented with communal property and ownership.

The cohousing model has also been criticised for excluding outsiders. The strong sense of community can be perceived as exclusive, and there are critics who have compared cohousing communities with gated communities – fenced and often prosperous residential areas that are separated from their surroundings. The effect of a cohousing community on a neighbourhood is very much about how communal spaces and functions relate to the surrounding streetscape and city.

In the exhibition What We Share, themes around ownership and participation are addressed in the film Å bygge en seng, Å bygge et hjem (Building a bed, building a home), by Anna Ihle.

The architecture in Nordic cohousing communities

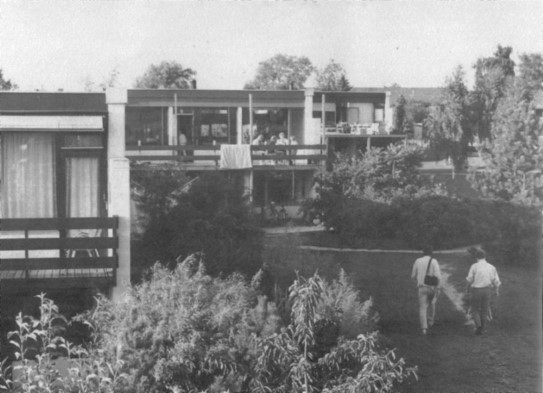

Cohousing communities come in almost all shapes and sizes. In Denmark, the previously mentioned cohousing communities Sættedammen and Skråplanet were based on small buildings with around 30 housing units. In Norway, the earlier cohousing communities varied greatly in size, from the high-rise block of Kollektivet Hovseter, with its more than 150 housing units, to the Havstein cohousing community (1986), with just three. Many cohousing communities are located in urban areas, such as Bergsligata in Trondheim, or Friis gate in Oslo, while others are more rural, such as Havstein and many of the larger Danish cohousing communities.

The architectural approach also varies. Some cohousing communities have been specially designed for the purpose, while others have been adapted, such as Kollektivet på Hovseter, which took over buildings that were originally designed for conventional apartments. The Danish projects in the 1970s were largely specially designed projects. It was not until the 1980s that several relatively ambitious architect-designed cohousing communities emerged in Norway.

Kollektivet Havstein (1986) in Trondheim, designed by Kjell Kristiansen for Ragnar Engh's architectural firm, was a specially designed cohousing community for three families. With a design language that drew on both Norwegian wooden house tradition and international postmodernism, the communal rooms were partly glassed-in areas, while the private living units were tailored for each family, built in wood over two levels, with both double height ceilings and split-level floors.

The Samba Bærumba cohousing community, designed by Planforum, was developed for a housing exhibition in Bærum in 1987. It consists of a row of six terraced houses with an inner, glassed-covered street, a communal building on two floors as an extension of the street, and glassed-covered gardens that were to serve as private buffer zones between the private and communal areas.

A third cohousing community with a distinctive signature was Villa Holmboe in Tromsø (1988). It was first designed by the architectural firm Blå strek and later completed by architect Gudmund Sundlisæter. A characteristic feature is a prominent tower in the corner of the building, which houses the communal functions in the project.

Common to these specially designed projects was a desire to give the housing form a distinctive architectural expression – and that the communal rooms in particular are emphasised architecturally. These are features that have been continued in several newer cohousing communities, including Helen & Hard's Vindmøllebakken in Stavanger, and not least in the new cohousing community developed for the Nordic Pavilion in Venice.

An expression of community

The cohousing community presented in Venice integrates all the forms mentioned above. It is based on a development process influenced by the residents, and has a volunteer-based form of community. It has an architectural design that both facilitates individual adaptation for each resident, and at the same time expresses a collective aesthetic. It emphasises the communal space as the most important, but through what are referred to as ‘sub-zones’ between the private unit and the communal space, the residents have the opportunity to express themselves and create distinctive social situations.

A method to achieve this is a new building system in solid wood which is used to construct both the building and the furniture, which the residents can build themselves. This creates a common landscape across the private apartments that can integrate many different wants, needs and personal expressions.

In the exhibition in the Nordic Pavilion, the building system is used for ‘traditional’ communal functions such as kitchen, sewing workshop, greenhouse and reading corner, but also more ambiguous zones such as hiding places for children or semi-public zones where apartments open up and become part of the communal space. This is how the boundary between the private and the public, the owned and the shared, is challenged. Since each resident has a sub-zone connected directly to their private unit, they have a new and greater responsibility to be active in this zone.

Tomorrow's cohousing community in the Nordic countries and beyond

Within today's housing market, it appears that housing projects, particularly the larger ones, are failing to meet the needs of the individual residents in the best way. There is rarely direct contact between architect and end user, and the homes are developed within standardised formulas and for average, hypothetical residents. When the future residents are allowed to participate already at the planning stage, the cohousing model can give each individual a role in the home-building process, even within larger commercial housing construction. By arranging for residents to meet and organise themselves in advance, they can take their place on the other side of the table, as developers and clients for the project.

In this way What We Share illustrates both a method and a building system which can be implemented within several potential cohousing models. It is a both a continuation and a further development of the Nordic cohousing community model.

Sources:

Lene Schmidt, Boliger med nogo attåt, Oslo: Husbanken 1991

Lene Schmidt, Nye boliger med ‘nogo attåt’, Oslo: NIBR 2002

T. Lange / S. Wahl Ekedahl, Fra servicehus til dugnadsfellesskap (From service building to volunteer-based community): Borettslaget Kollektivet 1976-2016

A. Eriksen / Joakim Skajaa (eds), Pollen # 2: Bofellesskap, Eriksen Skajaa Architects 2002

Bodil Graae, 'Børn skal have hundrede forældre' (Children should have a hundred parents)’, Politiken 9.4. 1967

Jan Gudmand-Høyer, ‘Det manglende led mellem utopi og det forældede enfamiliehus (The missing link between utopia and the outdated single-family house)’, Dagbladet Information, 26 June 1968.

Henrik Gutzon Larsen, ‘Three phases of Danish cohousing: Tenure and the development of an alternative housing form’, Housing Studies, Volume 34, 2019. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02673037.2019.1569599

Francesco Chiodelli, ‘What is really different between cohousing and gated communities?’, European Planning Studies, Volume 23, 2015.