The Collection presentation: concept and structure

In the new National Museum, for the first time you can explore works from different parts of the museum’s collection under one roof. The museum boasts almost twice as much exhibition space as the old museum buildings combined.

The collection exhibition presents some 6,500 works from Norway’s largest collection of art, architecture, and design – from antiquity to the present. Norwegian art, design, and architecture are shown here in an international context.

Chronologically arranged, the presentation introduces the distinctive features of Norwegian art up through history, in dialogue with foreign works from the collection. Here, various parts of the collection interact both within and across historical periods.

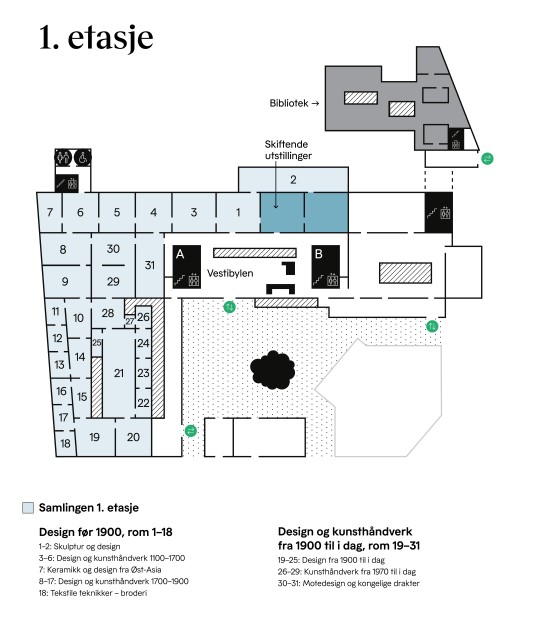

The collection presentation is structured in two main parts, which are arranged chronologically and thematically. The displays on the ground floor focus primarily on design from antiquity to our own era and crafts from 1970 to the present. Those on the second floor concentrate on visual art from the 16th century to the present. In addition, there are two rooms devoted to architecture.

The museum building

The brief for the architectural competition stipulated general guidelines for the space required for the collection presentation and the nature of the displays: rooms for the collection presentation should be neutral and flexible, spread across two floors, with a total of around 10,000 m2. In subsequent planning, the proposal was elaborated. The ground floor (design pre-1900, crafts, and fashion) has a series, or enfilade, of exhibition rooms of similar size, with smaller side rooms or cabinets. The solution encourages a principal direction of flow for visitors throughout the floor, with detours to the smaller rooms along the axis, a pattern familiar from 19th century museum buildings.

The second floor uses the same solution, but in three variants. The wing that was intended for older art up to 1900 uses the same enfilade principle with a series of interconnected main rooms and smaller side rooms. The rooms in the wing for modern art have a looser organisation, while the rooms for contemporary art, located towards the back of the last wing to the west, form a sequence of large rooms. Wide openings provide a view through the entire enfilade and a clear direction for the flow of visitors.

The main structure of the collection presentation

This two-part structure was chosen for a number of reasons. First, the floor plans and the dimensions of the rooms on the two floors dictate to a certain extent how the rooms are to be used. For example, the rooms on the second floor are more suitable for contemporary art and spatial installations due to their greater height, while the smaller more intimate rooms are better adapted to smaller format 16th-century paintings.

Secondly, the two-part structure makes it easier to emphasise the distinguishing qualities and development of the separate subject areas. Art, architecture, and design are created for distinct purposes, in distinct contexts. At the same time, where relevant, significant information about connections between subject areas is elaborated and emphasised on both floors. Architecture, for example, is included in several rooms that deal with the period 1900–1960, a time when artists, architects, and designers worked closely together.

The third reason for the chosen structure is that the National Museum’s collection arose from the merger of four earlier museums, each of which had its own policies and traditions for collecting. Accordingly, not all periods are equally well represented in all subject areas. For example, the museum’s collection of 18th century design is very rich, whereas the painting collection for the corresponding period is less extensive. As for the architectural collection, it dates back only to the early 19th century and is largely dominated by the 20th century.

Objectives and perspectives

The collection presentation illuminates the principle strands of Norwegian art history in an international context. The exchange of ideas and visual influences in art, architecture, and design takes place across national borders. The international perspective throws light on Norway’s place in the world and provides insights into different perceptions of Norwegian identity. A number of fundamental objectives apply throughout the presentation. It should reflect an awareness of each exhibit’s historical significance while catering to the needs and expectations of contemporary audiences. It should give visitors the opportunity to learn more about the respective subject and encourage relevant involvement and activity. The focus should be on the human element, both contemporary and historical.

Throughout the planning phase, the selection and distribution of works, the exhibition architecture, and the educational aspect have all been developed as mutually interdependent factors. Each room and theme was given a historical context in order to elaborate the framework in which the works were created. All art, architecture, and design are made by and for people and were once part of their own time. Art forms relate to human life and its various needs – spiritual, intellectual, and material. In this respect, they have played a role both in society and for individuals. The connections between politics, religious beliefs, identity, and the specific works are articulated at various places in and around the collection presentation. Artists, architects, and designers create our surroundings: the houses we live in, the cups we drink from, the art on the walls of our homes, churches, and town halls. As interpretative statements, they help to shape how we perceive the world. What has landscape painting meant for the way Norwegians relate to nature? Costume and fashion carry information about who we are or want to be. Architecture can be designed to create a pleasing environment. Contemporary art can explore current social and political issues.

The National Museum’s rich collection of art, architecture, and design contains a wealth of possible stories about the past and the present. The collection presentation seeks to convey knowledge that is both broad and deep, to highlight little-known works and stories, and to ensure broad representation. Emphasis has been placed on highlighting new perspectives, historical narratives, concepts, and ideas relating to art, architecture, and design. The exhibition rooms are varied in their design. In addition to the historical objects, they include everything from documentary films and archive material to soundscapes and interactive facilities.

Several rooms include displays that focus on the concrete and practical aspects of creating art, architecture, and design. These explore, for example, the training and professional lives of artists, craftsmen, and designers. Knowledge about the use of materials, technology, crafts, and innovation is also conveyed, e.g. in the form of films. A number of artists, architects, and designers receive particular attention. The same applies to certain private benefactors who have made significant contributions to the museum’s collection.

Ground floor

Design before 1900

The first room of the collection presentation – Face to face – introduces the theme of the human condition through history and in the present. Here the exhibition design brings the contemporary visitor together with people from the past, in the form of portraits from Greek and Roman antiquity, symbolically placing them centre stage. All around, one finds ceramic, glass, and textile artefacts that have accompanied people in their domestic everyday lives through to the grave. In addition to showing the back of the objects, the mirrors in the display cases allow the visitor to see their own reflection. Krigsdans (War Dance), a contemporary work by the Sami artist Annelise Josefsen, addresses the themes of faith, war, and cultural struggle, power, and powerlessness. The adjacent room (Room 2) features plaster casts of sculptures depicting gods and heroes from different cultures and historical periods.

Rooms 3–19 are dedicated to design, organised chronologically into eras. Rather than trace a narrative about the historical development of style, the presentation illuminates each era in terms of phenomena and events that have had an impact on art and industrial design in the respective period. There is an emphasis here, on the one hand, on the way contacts between different cultures and geographical areas lead to the exchange of ideas, ideals, materials, and techniques over time, and on the other, on the importance of the dialogue each era conducts with the past and the visions it nurtures for the future. At the national level, a culture of objects and artistic identity are often a fusion of external and internal influences, and elements from the past. These are interpreted and adapted to local needs and attitudes.

Rooms 3–19 cover a time span from the 12th to the 20th century. Here again there is an emphasis is on notable events and phenomena that have shaped European craftsmanship and design. Visitors will also learn about factors that have had lasting impact on artists, sometimes over several generations, such as Chinese arts and crafts, displayed under the heading Chinoiserie (Room 6). Another example is the evolution of majolica pottery as it migrated between cultures and geographical areas, and across time to become a contemporary craft (Room 4).

In Room 3, the overriding themes are the Church as patron and the work of the craftsman in the service of faith. Here there is also a separate section devoted to the museum’s rich collection of icons. The next room presents objects from the period 1500–1650. The invention of the printing press is explored as an important factor in helping to spread design and ornamentation trends among craftsmen. As ideas and ideals are made more accessible, they pass more easily across national borders.

Rooms 5 and 6 present the era 1650–1750, a time when Europe was systematically organising trade and the transport of new materials and objects across the world’s oceans. Access to new materials is of great importance, not least for decorative art and interior design. The period 1750–1800 is the subject of Rooms 8 and 9. Here the focus is on how the systematisation of nature and human activity during the Enlightenment is reflected in decorative styles and motifs, new methods of production and entrepreneurship.

Room 9 deals with Denmark-Norway as an economic and industrial entity. Here the exhibits include engraved goblets from Nøstetangen glassworks. The next room examines the close connection between politics and design in the period 1800–1850. Revolutions, powerful nations, and democratic ideas find reflection in design. Once again, people look back to antiquity, their political views often determining whether they give precedence to the imperial structure of ancient Rome or the democracy of the Greek city-state.

The period 1850–1900 is covered in Room 14. During this turbulent era, industrialisation and urbanisation led to major social upheavals. Mechanical production replaces the old guild system. The industrial art movement emerges to address the social challenges resulting from explosive population growth. One ambition is to improve people’s living conditions. Another is to raise the artistic quality of industrial products. The movement’s primary goal is to create good environments for people to live in.

Industrialisation and the decline of the craft guilds lead to professional and social tensions. Which approach to manufacturing is best suited to address the aesthetic and social challenges: mechanical or manual production? This is the crucial question during the period 1880–1910 (Room 15). This part of the collection presentation concludes with the situation in Norway during the years 1900–1920. With its jubilee exhibition in 1914, Norway celebrates its own arts and industries as a modern, independent nation. This is a period when the art and design community is preoccupied with the quest for national identity.

Design from 1900 to the present

Three large rooms are devoted to design under the titles The search for the modern (Room 19), Ideals, crisis and growth (Room 20), and Designing identities (Room 21). They explore the role of design in society and culture, movements and phenomena from the history of design, and the ideas, ideals, and ideologies that went with them. One of the tenets behind these displays is that design is charged with meaning. About a third of the objects in the design presentation are new acquisitions.

Furniture and interior design, industrial and graphic design, textiles, and fashion are presented chronologically with reference to selected themes, in some places with interventions from other periods. The objects are considered in relation to each other, sometimes against the background of works from other disciplines, such as fine art, architecture, photography, and crafts. The emphasis is on Norway as seen from an international perspective.

Further narratives about the production, transmission, and use of design are traced in a series of smaller rooms. The first, Instant impact (Room 22), is about graphic design, illustration, book-making crafts, etc., and considers everything from posters to the new Norwegian passport. In the room Materials and responsibility (Room 23), visitors are able to get closer to the objects via material samples that they are invited to touch. The room From product to service (Room 24) shows an industrial designer’s workshop. A separate commissioned work, Orchestrated Experience, interprets service design. The last room, Screen time (Room 25), turns the spotlight on the graphic aspect of our digital environment.

Crafts from 1970 to the present

Rooms 26–29 show crafts from 1970 to the present. Norwegian crafts have a strong standing in the Nordic region. Norwegian makers and educational institutions are internationally oriented, thanks not least to a policy in the arts education sector of recruiting teachers from abroad. This has fostered a diverse craft scene and helped many practitioners to establish international reputations. The introduction to crafts covers everything from traditional practices that place the emphasis firmly on manual skills and the production of functional artefacts through to conceptual practices that treat manual skill and functionality on a more abstract level. The presentation juxtaposes Norwegian crafts with the work of makers elsewhere in the world, primarily the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Netherlands.

Art enters everyday life (Room 26) looks at works by practitioners of significance for the crafts scene both in Norway and internationally. In addition, the displays consider the different approaches adopted by artists and how they progress from the concrete to the conceptual. A separate room, Wearable art (Room 27), is devoted to art jewellery. Here, visitors can discover a spectrum that stretches from sculptural to conceptual works by both Norwegian and international jewellery artists. Room 28 is entitled Containers: bowls, vases, mugs, jugs, and cups are not just essential household objects, they can also be important as political and religious objects. This display explores how Norwegian and international craftspeople approach the basic idea of the container from the angle of form, decoration, and concept. The final room in this section is History is now (Room 29). This room features works by Norwegian and international makers who use tradition and history as a source of inspiration to comment on their own traditions and practices, and the contemporary era.

Costume, textiles, and fashion

The collection presentation includes a rich section on costumes, textiles, and fashion. Throughout history, textiles have been an important and valuable commodity that people associate with significant events in their lives. One objective has been to display textiles, costumes, and accessories alongside other object categories in the presentation. In several rooms, textiles and costumes are juxtaposed with paintings that contain notable depictions of the fashion of a period (Rooms 5, 6, 8).

When it comes to textiles, especially the oldest examples, there is considerable uncertainty about who made them, where the work was done and how they entered the museum’s collection. Often it is only fragments that remain, as is the case with the oldest textiles in the collection, which are elements from costumes found in ancient Egyptian tombs (Room 1).

Norway has a long and rich tradition of textile art, and the National Museum’s collection has finds and objects that represent a period of nearly a thousand years. On display in Room 3 is the Baldishol Tapestry, together with chasubles and other wall hangings.

Around the mid 16th century, Norwegian tapestry undergoes a renaissance. Artisans from northern German and the Low Countries bring fresh knowledge to Norway. It was now possible to weave tapestries with vivid, realistic depictions of scenes involving perspective and depth effects similar to paintings (Rooms 5 and 6). Gradually, distinctive themes are developed that become more stylised and abstract, thus steadily increasing the importance of ornamentation as a form of expression in tapestries.

Starting around 1900, textiles in Norway undergo substantial development as the field is professionalised and strengthened. In particular, folk costumes become an important marker of political attitudes among women. The extensive presentation in Room 19 provides insights into women’s fashion around 1900, a period of significant change during which fashion ideals responded, for example, to influences from Japan.

The room with contemporary fashion, A rising nation of fashion (Room 30), is designed to accommodate temporary exhibitions while maintaining a chronological narrative. The focus is on Per Spook, a Norwegian fashion designer with an international career. Also on show are examples of works by Norwegian designers that explore the borderland between fashion and art. Film and sound are used to convey a broader sense of the complex world of fashion. With contemporary fashion as one of its areas of specialisation, the National Museum has significantly expanded its collection in recent years with the purchase of creations by several key fashion designers.

Under the heading Two queens meet, Room 31 is devoted to unique items from the royal costume collection, which is managed by the National Museum. Here, visitors get to know Norway’s two queens of modern times, Queen Maud and Queen Sonja, via selected outfits from their wardrobe. The display highlights the link between the costumes and the monarchs’ official duties.

Second floor

Art 1500–1860

The second floor offers a chronological and thematic presentation of art from the 16th century to the present. The first six rooms (Rooms 33–38) are devoted to older European art up to ca. 1800. The significance of religion in people’s life is addressed in the rooms Images for faith and devotion (Room 33) and Creating light in darkness (Room 37). On display are works by major artists including Lucas Cranach, Orazio Gentileschi, and Artemisia Gentileschi. Separate rooms take a closer look at mythology, and the still-life and landscape genres (Rooms 34 and 35).

Portraits, depictions of specific people, are a genre that crops up in various places throughout the collection presentation. The room entitled Looking back (Room 36) features a number of 18th century portraits. Most of the works on display originate from areas that are today in Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Denmark, and Norway. Many of them were acquired in the years immediately after the founding of the National Gallery in 1837, and can be regarded as examples of the older European art canon. This part of the collection was further strengthened by a significant bequest from the art collector Christian Langaard, a donation that is honoured with a room of its own (Room 38).

As early as 1839, the National Gallery began to purchase contemporary Norwegian art, including works by Johan Christian Dahl and Thomas Fearnley. From around 1850, the Norwegian portion of the collection grew in parallel with the development and professionalisation of art in Norway. Foreign artists either visited or established themselves in Norway, and Norwegian-born artists went abroad to study and work. These themes are addressed in rooms such as Wild nature, tamed landscapes (Room 39), The making of an artist (Room 40), and Journeys of discovery (Room 44).

Norwegian landscape painting is especially well represented. It is supplemented by examples of the genre from other countries. An entire room is devoted to the work of Johan Christian Dahl (Room 42). Coastal scenes, primeval forests, and mountains feature in Rooms 46 and 47, as depicted by Hans Gude, Kitty Kielland, Lars Hertervig, and August Cappelen. For the young nation-state of Norway, a rich cultural life was considered politically important as factor that would help in the aim of nation-building.

The Norwegian peasant as a living connection to the past is the theme of True to tradition (Room 45). The principal artist here is Adolph Tidemand, whose work is considered in relation to comparable artists in other countries. The room brings together a variety of subjects and historical periods. Here one can see design objects that reflect peasant traditions back in time, but also the traditional costume, the bunad, that is still worn today on festive occasions. Duodji, the aspect of craft and design in Sami applied art, is also a vehicle for tradition. Our examples of contemporary duodji are loaned from RiddoDuottarMuseat in Karasjok.

Art 1860–1920

The latter half of the 19th century is a rich period in Norwegian art and cultural life. This is reflected in the National Museum’s collection, where the dominant trends in Norwegian art are well represented. The increasing awareness of national identity led to greater interest in Norwegian and Nordic history, and Norse mythology. Fairy tales, legends, and other immaterial folk culture constituted a major source of inspiration. These themes are explored in the rooms History and mythology (Room 49) and Once upon a time … (Room 64). Norwegian nature is a central theme throughout the period. In addition to the naturalistic landscape, this section also highlights more atmospheric approaches to the genre, as exemplified by Harald Sohlberg’s Winter Night in Rondane (Room 61).

One of the declared objectives of the collection presentation is to highlight the human aspect of artistic creation. Accordingly, the room Among the artists (Room 52) is devoted to portraits of important people in Norwegian cultural life. It was during the 1880s and 90s, that Edvard Munch rose to prominence, and in the new National Museum we continue the National Gallery’s tradition of dedicating an entire room to his work (Room 60). Another artist with a room of her own is Harriet Backer (Room 51). Art that lends its voice to social and political causes is the subject of Stand up for justice (Room 57). One of the works on show here is Christian Krohg’s famous Albertine painting.

The museum has a substantial collection of 19th-century French art, and the cultural dialogue between France and Norway forms the theme of the rooms To Paris (Room 53) and A revolution in painting (Room 54). Around 1900, the idea of erasing the boundaries between different art forms began to find a following. Painting, sculpture, and industrial art should be merged into one, the ideal being a close collaboration between artist and artisan. A selection of Norwegian examples of such collaborations is presented in Art in everything (Room 65).

Considerable energy was invested in sculpture on the Norwegian cultural scene in the 19th century. The language of the body (Room 55) shows works by Menga Schjelderup-Ebbe, one of the few female sculptors in Norway at this time. A selection of Gustav Vigeland’s works are presented in Moods and emotions (Room 61).

Art 1900–1960

Edvard Munch was also closely involved in the radical changes that affected the visual arts around the beginning of the twentieth century. In Life force (Room 63), we encounter vitality and vigour in abundance. It is evident in everything from the farmer in his blue overalls, his lap overflowing with the fruits of the earth, to the boys at play, reaching for the sun.

The first half of the 20th century was a period of rapid development for the art collection. Thanks to generous donations from private collectors such as Olaf Schou and foundations such as the Friends of the National Gallery, the museum acquired outstanding works by modern masters such as Berthe Morisot, Edvard Munch, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso.

In the rooms Expression (Room 67) and Fragments of reality (Room 68), we learn more about the experiments conducted by leading artists of the period in their search for new forms of expressive sincerity. Intense colours, a coarse approach to depiction, and the beginnings of a rejection of mimesis and pictorial illusionism prepare the ground for an exploration of the irrational world of the human imagination and for pure abstraction.

The complex reactions to war and modernisation during the inter-war period form the theme for the next set of rooms: Modern times (Room 70), Black Birds (Room 72), and Man and society (Room 73). In What shall I fight with? (Room 74), the tapestries of Hannah Ryggen and the paintings of Arne Ekeland confront us with the growth in politically active art. Under the title After the great disaster, the breakthrough of abstract art and the situation after World War II are the themes of Room 75.

Art from 1960 to the present

Although the former Museum of Contemporary Art mounted a number of exhibitions based on works from its collection, the museum never had a permanent presentation of its holdings. The sequence of rooms devoted to contemporary art in the new National Museum is therefore an innovation. The presentation introduces central isms and trends from the mid-1960s through to 2014, including pop art, conceptual art, process art, and arte povera. Less radical tendencies, such as the dynamic resurgence of painting during the 1980s, are also addressed. The presentation is chronological and has an emphasis on Norwegian artists (71.7%).

In On the barricades (Room 76) the focus is on the political and activist art that emerged in the 1960s and 70s. This is the era of protest marches and liberation struggles. The dominant causes of the period were those against capitalism and Norwegian membership of the EEC, and those in favour of environmental protection, women’s rights, and Sami rights. New artistic strategies such as assemblage, performance, rustic weaving, and hard-edge graphics are introduced to a Norwegian audience.

Optical shock (Room 78) is devoted to the concrete, kinetic, and op art of the 1960s and 70s. In painting, the innovations include vibrant optical illusions and geometric surface structures. Driven by an interest in the psychology of perception and colour theory, these optical works transform the visual artwork from a static object to an event that the viewer helps to create. In room 81, works from the National Gallery's collection and the Robert Meyer Collection are combined. With their sensorially stimulating materials, such as straw, ice, and tobacco leaves, these works are given an entirely new setting in the museum’s white-cube room.

Close relatives of arte povera are conceptual and process art, on display in Room 82. The title of this room, Odds and ends called art, is taken from a disparaging newspaper review, illustrating the conservatism this kind of art had to contend with in Norway in the 1970s. Norwegian pioneers are presented here side by side with international names.

Back to painting (Room 84) addresses the return to figurative painting, with an emphasis on the 1980s. Some of the artists of this period drew inspiration from the Italian transavantgarde and surrealism. Others created works that can perhaps best be described as a kind of romantic postmodernism. In A Nordic miracle (Room 85), it is the transition from analogue to digital photography and the breakthrough of video art in Norway and the Nordic countries that sets the tone. Truth versus manipulation, identity, and the abject are some of the themes that are highlighted.

Recycled revolution (Room 86) takes a look at one of the most significant isms in Norway during the early 2000s: neo-conceptualism. Filled with works based on appropriation and quotation, this room takes a sideways glance at the present and the recent past. The last room in this section (Room 87), Wrestling with clay, considers the resurgence of ceramics and its successes in recent years. Wearing 3D glasses, you can slither into a Gutai-inspired mud wrestling match or admire enormous ceramic dishes.

Three installations create a break in the otherwise chronological presentation. The first is the museum’s ambitious reconstruction of Norway’s first major multi-media sculpture: Irma Salo Jæger’s kaleidoscopic Glance, which is accompanied by the music of Sigurd Berge and the poem Blikket (Glance) by Jan Erik Vold (Room 80). In Ilya Kabakov’s The Garbage Man (The Man Who Never Threw Anything Away) (Room 83), visitors are transported back to life in a Soviet communal apartment, a komunalka. The installation contains 400 drawings, texts, objects, and scraps of garbage. Originally made for the Museum of Contemporary Art at Kvadraturen, Oslo, the work has been reconstructed down to the smallest detail in the new National Museum. The third installation is Per Inge Bjørlo’s Inner Space V. The Goal. Also originally constructed for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Bjørlo’s claustrophobic installation remains unchanged, with the exception of the entrance, which the artist has redesigned to give a rougher feel (Room 88).

Architecture

Two rooms with a primary focus on architecture are included in the chronological presentation on the second floor. How we want to live (Room 66) shows how the architects of the 1920s and 30s developed visions for better living through the design of homes, restaurants, and open-air baths. This section builds on models from the Harald Hals collection. Architect Sverre Fehn and his buildings for the presentation of art are explored in the second room (Sverre Fehn – spaces for art, Room 77). Large photographs of Fehn’s pavilions in Venice and Brussels cover two of the walls, creating, in combination with the skylights, a sense of being present in these buildings. Both spaces use elements of fine art and design.

Works from the architecture collection also occur in other contexts on both the first second floors. Journeys of discovery (Room 44) and Modern times (Room 70) feature works by Carl-Viggo Hølmebakk, Lars Backer, and Ove Bang. The presentations on the ground floor integrate works by, among others, Christian Heinrich Grosch (Room 11), Henrik Bull (Room 19), Arne Korsmo, Bjercke and Eliassen, Blakstad & Munthe-Kaas (all in Room 20), and Jan & Jon (Room 21). All these architects are well represented in the museum’s architectural collection. The presentation includes drawings, photographs, models, and section of building.

Learning

The aim has been to provide visitors with a variety of ways to view and interpret the objects on display and to offer a broad range of material to appeal to a diverse audience.

Zones for relaxation, immersion, and participation have been integrated with the exhibition. The collection presentation includes various educational aids in the form of texts, images, audio material, and hands-on learning activities. Many rooms have dialogue cards with philosophical questions, also in Braille, and objects that can be touched. A few rooms provide facilities for visitors to draw.

Exhibition architecture

In 2016, the National Museum announced an international competition for the exhibition architecture and the design of the collection presentation. The contract was won by Guicciardini & Magni Architetti, a company based in Florence. The main architect was the partner Marco Magni, who brought in his own employees to carry out the work.

For this commission, Guicciardini & Magni Architetti developed a design concept that establishes visual and content-related links between the exhibition areas on the ground and second floors. This helps to reinforce the overall concept and appreciation of the works of art and the various educational elements in the rooms. The design concept was developed to blend with the architecture and materials of the museum building.

Representatives from Guicciardini & Magni and their subcontractors have been engaged in a creative collaboration with the National Museum’s staff since the summer of 2016. In addition, the exhibition architects were responsible for the design of display cases and exhibition furniture, such as plinths and seating. They also developed a colour palette for the rooms in the collection presentation. Together with the graphic design of the information panels, these elements form a unified whole. Lighting design is also integral to the exhibition. It supports suggested lines of interpretation, creates variation both chromatically and in terms of brightness, and is a factor in meeting conservation requirements.