Use the menu to jump between sections

Wilhelm von Hanno (1826–1882)

In the 19th century, Wilhelm von Hanno was one of Norway’s most important and prolific architects. It is difficult to walk far in Oslo without encountering his architecture. Originally from Germany, von Hanno emigrated to Norway as a newly qualified architect.

Von Hanno worked as a stone mason, draughtsman and architect. He had studied under the architectural painter Martin Gensler, and in Christiania (now Oslo) he ran his own drawing school, which made an important contribution to artistic and architectural education in the city. He was also responsible for the design of Norway’s posthorn postage stamps. Designed in 1871, these stamps are still in use today.

The Trinity Church

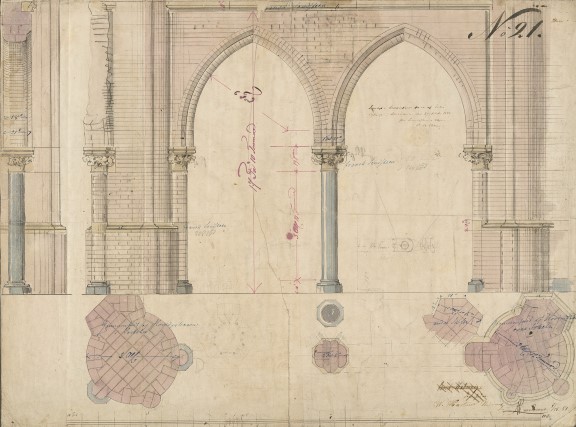

Following a lengthy and arduous process, Trinity Church was completed in 1858. Until then Our Saviour’s Church (now Oslo Cathedral) had been the city’s only church, but it had become too small for the growing congregation. In 1849, the city invited five architects to submit designs for a new church. This was probably the first architectural competition held in Norway. The city awarded the commission to the celebrated German architect Alexis de Chateauneuf (1799–1853), based in Hamburg, whose wife was Norwegian.

Chateauneuf proposed an octagonal central-plan church crowned by a monumental dome. The central space beneath the dome interior was surrounded by a vaulted colonnade supporting the gallery, which also created a symbolic transition from the dark entrance to the light-filled nave.

The Christiania Fire of 1858

Grønland

Grønland was incorporated into Christiania in 1859, generating a need for public buildings in the city’s newest district. The city authorities decided to build a combined fire-and-police station, a school and a church. A competition for all three buildings was announced in 1864. Von Hanno and Schirmer submitted separate proposals, thus marking the end of their long-standing partnership.

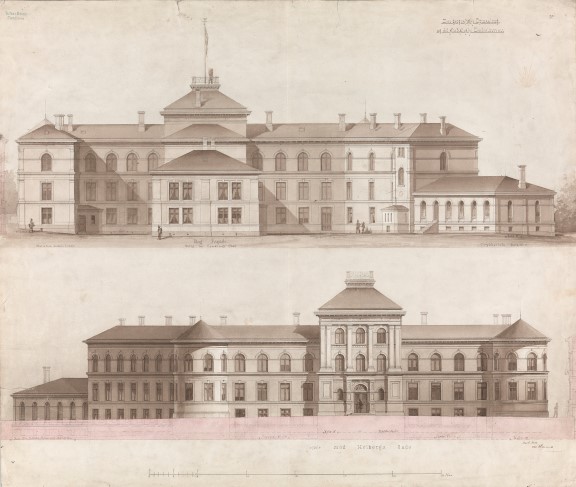

The Geographic Survey of Norway

As early as the 1850s there were proposals to erect a dedicated building to house both the National Archives and the Geographic Survey of Norway (now the Norwegian Mapping Authority) at Tullinløkka, close to the Royal Palace. Three architects, including von Hanno, were invited to submit proposals.