The idea that buildings can have a national identity is relatively modern. Internationally, the 19th century fascination with different cultures led to an increasingly intense focus on national styles. The question of what was national, and why, was debated all over Europe.

In Norway, the mediaeval period was quickly identified as a golden age, an era of national power and independence. Stave churches and farm buildings made with a notched-log construction (lafting) became national symbols.

While contemporary perceptions about what is national are ever-changing, many 19th-century ideas about what makes a building Norwegian still hold true today. ‘Dragons and Logs’ presents this history through drawings, photographs, models and paintings.

Until 1850, many people thought of stave churches as impractical and primitive. The painter Johan Christian Dahl was among the first to recognize their importance and went on to make them famous both in Norway and also the rest of Europe. When the stave church in Vang was going to be pulled down, attempts to save it by moving it to another site in Norway were unsuccessful. Instead, Dahl succeeded in preserving the church by selling it for transport abroad.

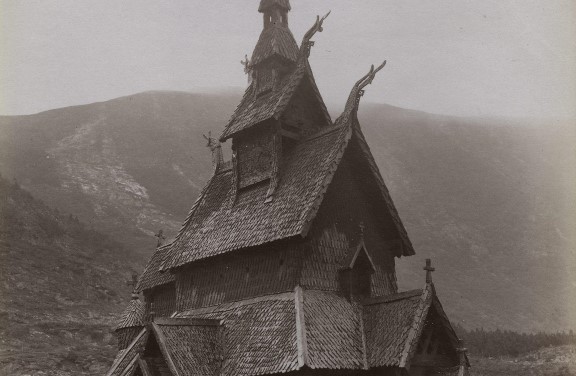

The stave churches’ status rose very rapidly and by the 1860s, Borgund Stave Church was considered the most authentically Norwegian of all. A magnificent model of the church was used to market Norway abroad.

Architecture was one of several important aspects of cultural and political nation-building efforts in the young state of Norway. The stabbur (a traditional farm storehouse on pillars) was adopted as an archetypal Norwegian building, and buildings that included animal ornaments, decorative roof ridges and stabbur-like designs were declared to be in the ‘old Norwegian style’, today more often known as the ‘dragon style’.

Throughout Europe, folk cultures were widely believed to be the repositories of the ‘authentically’ national. Peasants were seen as guardians of the essential qualities of different national identities and in Norway, the archaic building types found in rural areas were seen as directly linked to the age of the Viking sagas. On field trips to farmsteads in eastern Norway, the architect Hermann Schirmer instructed his students in how to study old building customs and how to use these traditions in their own work.

The age of the Viking sagas and the Middle Ages attracted international interest. At the Paris World’s Fair in 1889, history and marketing were intertwined. Models of pre-fabricated buildings produced by Thams, a company based in Orkanger, were displayed alongside models of Borgund and Heddal Stave Churches.

National styles could also be used for overtly political purposes. A chapel built at Njauddâm / Näätämö / Neiden in the far north-east of Norway, very close to the border, was designed in an obviously stave church-like style. The building was intended both as a marker of Norwegian territory and as a means to assimilate indigenous Skolt Sámi and Kven people into mainstream Norwegian culture.